I believe that Gay Ann Rogers is one of the U.S.’s most extraordinary embroidery designers and stitchers. Many of her followers delight in her combination of history and fiber art as seen in her exquisite portraits of famous figures (especially royalty) and of scenes she refers to as “samplers.” Her series of “hearts,” “cameos,” and needle books attract stitchers from the far reaches of the globe. I have always admired Gay Ann’s work and have followed her blog for several years. It’s so much fun to read. (www.gayannrogers.com)

But it is her latest “portrait” of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony that has grabbed my heart, and it has become a goal of mine to stitch it. As a sidenote, let me just add that I am a women’s historian by profession and an embroiderer as well. Since the 1970s, I have created and stitched what I call political posters in my collection, “Stitcherhood is Powerful.” Among my recent pieces are ones that aim to educate people about notable women in U.S. history. (You can see several of these pieces on my website, http://harrietalonso.com.)

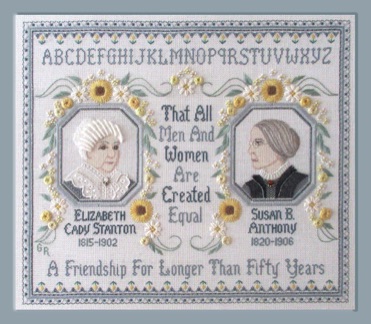

In her piece, Gay Ann decided that she wanted to honor her two heroes for their creation and leadership of the 19th century movement to achieve women’s rights as well as their friendship which lasted more than fifty years (give or take a few times out to argue and avoid each other). You can read all about Gay Ann’s journey in developing the piece by clicking on “My ECS/SBA Story” on her website. There she explains how the project evolved including the adaptation of the 19th century sampler style.

I find the elements of the design truly engaging. In the center, Gay Ann adapted an image of each woman from actual photographs from their time. The portraits tell us so much, not only about the women but of Gay Ann’s perception of them as well. On the right is Susan B. Anthony. She is looking towards Elizabeth Cady Stanton and has a stern look on her face. Anthony was definitely the more conservative of the two women. She came from a Quaker family and lived much of her life in upstate New York. Her style of clothing, hair style, and outlook on life reflected her Quaker roots. Anthony never married (at a time when it was expected a woman would) and had no children. Some historians think that her background played into her stern demeanor. However, I found in my own research that she was far from being a prude. Children in the inner circle of the early woman’s rights activists often called her “Aunt Susan.” They looked forward to her visits and as they matured, to her wise adv

Elizabeth Cady Stanton is often characterized as the “brains” and philosopher of the pair while Anthony was the organizer, the person with boots on the ground. And while Anthony did do much of the running around to organize the movement’s actions, both women did all things….organizing, speaking, writing, raising funds, etc. However, Stanton had seven children and a not-so-cooperative husband, so Anthony often added babysitting to her work so that Stanton had time to compose speeches and articles. Gay Ann’s image of Stanton is softer than that of Anthony. In actuality, Stanton was far more radical than her friend in her lifestyle, enjoying socializing and fashionable clothes. She was more willing to try out a bloomer outfit than Anthony was, for example, though both women embraced some of the more adventurous health regimens----health foods, dress reform, physical exercise (to a point), and certainly not drinking alcohol or eating any product which was raised by slaves.

Stanton and Anthony met in 1851, three years after the first Woman’s Rights Convention in the U.S. was held in July, 1848, in Seneca Falls, New York. It was there that Stanton and others drafted the “Declaration of Sentiments” which was a woman’s version of the “Declaration of Independence.” Stanton insisted on the inclusion of the phrase, “that all men and women are created equal,” and it was that sentiment that drew Anthony into the movement and tied the two women together for more than fifty years. For me, the most important thing to remember is that for Stanton and Anthony, the goal was not just the vote, but true equality for women and then an end of all violence against women. Equality for them (and us, I hope) meant that women would no longer be held down by physical, political, economic, social, and personal abusive practices. I imagine if they were still alive, they would be out on the streets campaigning for the long- delayed ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Among the most joyful Moments of my sampler, it brought me Harriet Alonso.

And to my delight we began corresponding. Harriet is a rarity: she is a Professor Emerita of History at the City College of New York and she is an avid stitcher! Below is an essay she wrote for me to include with the instructions for my ECS and Susan B. Sampler. Thank you, Harriet!